Contents

Dr. Albert Abrams : Home Page

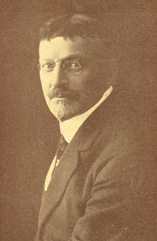

Dr. Albert Abrams (1863–1924). Unlike most of the purveyors of fraudulent or questionable medical devices of the time, Albert Abrams was a qualified and even highly respected physician. Born in San Francisco, California, in 1863, Abrams was an unusually bright youngster who learned to speak German at an early age. He relocated to Europe, where he received his medical degree from the University of Heidelberg at the age of 19, becoming one of the youngest men ever to receive such a diploma from the school. Upon returning to the United States, he studied for and received another medical degree, this time from Cooper Medical College in his hometown of San Francisco. Outgoing, energetic, and a gifted communicator, he was soon publishing an impressive array of medical papers as well as a textbook on heart disease. He joined the faculty at Cooper Medical School as professor of pathology, also serving as vice president of the California Medical Society. Ironically, in one of his early published articles, he even attacked the medical quacks so prevalent at the time, writing: “The physician is only allowed to think he knows it all but the quack, ungoverned by conscience, is permitted to know he knows it all: and with a fertile mental field for humbuggery, truth can never successfully compete with untruth.”

How the man who wrote those words could soon join the ranks of the “humbuggers” is something of a mystery. However, even before Abrams became known as one of America’s best known medical quacks, some onlookers had already questioned his moral character. Some sources report that his eventual departure from the faculty at Cooper Medical School came about from his questionable practice of throwing together skimpy lectures for his classes and then charging the same students $200 to attend more imposing private lectures in his home. There were also rumors of substantial and unaccredited “borrowings” from others’ work in some of his papers and articles. Perhaps the first hint of Abrams’s downhill journey came in 1909 with his adoption of “a new medical theory” which he called “spondylotherapy.” In books and articles he published on his new ideas, he claimed that by using this theory, which consisted of a careful and steady hammering on a patient’s spine, the practitioner could not only diagnose a patient’s illness but also cure it. Soon, despite criticism from other medical authorities (which he sometimes cleverly reworded to use in his advertising), he was giving lectures on “spondylotherapy” around the nation.

Needless to say, while his stock went up among a steady collection of gullible listeners, it correspondingly went down in the minds of his once-respectful fellow physicians. Abrams’s real break with orthodox medicine came, though, with his invention of the “dynamizer” and “oscilloclast” and his discovery of what he modestly called the “Electrical Reactions of Abrams,” or ERA.

“The spirit of the new age is radio,” Abrams wrote, announcing his discoveries, “and we can use radio in diagnosis.” Soon, linking his two inventions together, the dynamizer for diagnosis and the oscilloclast for the cure, he was claiming to be able not only to diagnose, but also to cure, all who came forth to try his amazing discoveries. Coming forth were many, for, like most of the quacks whom Abrams had attacked in his younger days, his wonderful black boxes, he claimed, were able to cure just about anything. Not only could cancer, diabetes, ringworm, pneumonia, and hundreds of other dark scourges of humankind be diagnosed and cured, but so sensitive were his machines that they could even reveal an absent patient’s age, sex, and religion.

The key to the success of Abrams’s black boxes lay in his promotion of his theory of “electrical vibrations,” which he claimed emanated from the cells in the body. When disease or illness befell the body, different vibrations were emitted according to the nature of the disease or illness. His dynamizer and oscilloclast were able to pick up the various “vibrations” “broadcast” from the body, measure their electronic frequency, and then broadcast corrective signals back to the patient. Most important, Abrams said in his advertising, all this could be done with a simple sample of the patient’s blood, taken at any time and at any place, provided that the patient was facing west at the time the sample was taken. Why it was necessary for the patient to face west Abrams never explained. Nor did Abrams explain his later claim that his remarkable devices could function by substituting the patient’s autograph or the sound of the patient’s voice over the telephone, in lieu of a blood sample.

Abrams may have been pushing the bounds of credulity a little too far with that last claim, but outside the legitimate scientific and medical communities and a handful of skeptics, apparently few were bothered by it. Abrams, always shrewd when it came to financial matters, not only treated patients himself but leased his sealed devices to other questionable practitioners. At one point 5,000 of his leased devices were in operation in various locations around the world. If any of the unsuspecting dupes or quacks who leased his devices broke the seals to examine inside the boxes and were surprised at what they found (or did not find), apparently no one complained. No one, that is, until Abrams’s burgeoning medical empire caught the attention of the American Medical Association and Scientific American magazine. During 1923–24 both groups spent a considerable amount of time investigating Abrams’s theories and devices. Taking his first look at the jumble of wiring and odds and ends inside one of Abrams’s boxes, the noted physicist Robert Millikan commented, “They are the kind of device that a ten-year-old boy would build to fool an eight-year-old.” Like most medical quacks, though, Abrams had plenty of defenders willing to endorse his ideas.

Noting that, in 1922, Upton Sinclair, famous author and defender of many strange ideas and medical fads, had written a laudatory account of Abrams and his devices for a popular magazine, the editor of Scientific American observed, “His name carried a brilliant and convincing story to the masses, who quite overlooked the fact that Sinclair’s name meant no more in medical research than [famous prizefighter] Jack Dempsey’s would mean on a thesis dealing with the fourth dimension.”

Ending their investigation in late 1924, a blue-ribbon committee of Scientific American concluded that “at best” Abrams’s ideas and devices were “an illusion,” and at worst “a colossal fraud.” The panel also noted that continuing advances in radio and electricity “had given rise to all sorts of occultism in medicine.”

For Abrams, though, the results of the investigations hardly mattered. A multimillionaire, he died of pneumonia a few months before the committees concluded their investigations. He was 60 years old.

Hundreds of his devices were still in use years after Abrams’s death. Not long before that, he had set up a foundation to carry on with his theories and devices, and today, unfortunately, many of them remain in use, updated with new technologies and contemporary “buzz words,” continuing to defraud the unwary.